A Media Project I completed during my Masters. Focussing upon the use and representation of memory within the successful first-person-shooter game, Call of Duty. Discussing concepts like synthetic memory, nostalgia and the contemporary representation of warfare within modern day media.

Media is able to make connections with the memory of the past through multiple forms, whether this be through the use of photography, film, or television. History has been a favoured genre for all these forms of media and is ‘a reductive exercise of capturing the evidence of the past and transcoding it into an assimilable narrative’ (Chapman, 2013: 323). Being one of the most popular forms of media entertainment, video games are often labelled as a medium for leisure. As video games began to filter into mainstream culture, they evolved from being tools of leisure to become methods of education and more. Huntermann and Thomas (2010) stated that is more often than not labelled as a form used for either distraction or release and push the notion that there are other ways in understanding this form (p.12). Video games have become a popular medium in which to capture and represent the past, more specifically the representation of war. Niemeyer (2014) states that ‘the contemporary representation of warfare is probably one of the most intense sites of dichotomy between and interpenetration of the persistence of a ‘mainstream’ news media’ (p. 239). However, regardless of its intense nature, there has been little investigation made into the interrelation between video games and cultural memory. With one of the most popular selling games of all time is based on warfare, the widespread popularity of the game raises some important questions. The first being, how accurate is the representation of war within video game such as this? And do these representations obscure existing memories we have of war?? Using Call of Duty as a primary source of reference, this project shall discuss and explore these questions as well as other theories which will shed light on the significance of video games and its relation of war and memory.

The origins of memory studies have been embraced by multiple theorists. Scholars from various fields have discussed the concept of memory, Durkheim highlighted the social aspects of memory, arguing memories are socially constructed rather than an aspect of our subconscious. If we use this definition provided by Durkheim (cited in Wilson, 2006: 3) alongside the perspective of memory is a way for people to recall the present in the present, then we can then assume memory to be subjective. ‘Memory, that is, like subjectivity, means different things and is understood in different ways at different times’ (Radstone and Hodgkin, 2003: 2). According to Assman (2008), memory can be present in the form of cultural memory, which is ‘built on a small number of normative and formative texts, places, persons, artefacts, and myths which are meant to be actively circulated and communicated in ever-new presentations and performances’ (p.100). Memories are able to exist within cultures through the gesture of communication, allowing memories to be shared through generations. Assman goes further to state that cultural memory has been a defined form of memory that is maintained via either cultural formation (monuments, texts, scripts) or through institutional communication (observations). As a result of these formations and communications, this indicates that memories have the potential to be timeless, ‘its horizon does not change with the passing of time’ (p. 129). In a sense, moments of memory are taken and temporarily frozen within time and can also be accessed throughout time, ‘form “islands of time” which allow for moments of memory to be temporality suspended from time. ‘In cultural formation, a collective experience crystallises, whose meaning, when touched upon, may suddenly become accessible again across millennia’ (p.129). For example, memorials for those who have fallen at war are a prime example of how memories of those have died have been preserved within society and can be called upon at any given moment. This example of memory is not to say that every medium will represent the same image in the same way nor does it claim that all memories are perceived in the same universally. Rather, it implies that each medium provides an alternative way of preserving and presenting memory. Not only does this suggest that an event, such as the World Wars, provide memories that can be shared within various culture throughout time, but also these memories of war can differ depending on either the culture in which they exist or the medium in which they are projected. The memory of war is able to be suspended in time, allowing for those who may not have a physical experience of the event to obtain and internalise memories. In addition to memories having the ability to be timeless, this then enables various forms of media to take advantage of these cultural ties and reimagine moments of history.

The Virtual Gun

The combining of video games and warfare have been a common pairing, the considered first of such being created at the beginning of the 1980’s. More recent releases of war-related video games are relatively new technological innovations, nevertheless they hold deep connections with culture, ‘given that modern technology has evolved in such a world of interacting economic, political, and military institutions, it should not come as a surprise that the history of computers, computer networks, artificial intelligence, and other components of contemporary technology is so thoroughly intertwined with military history’ (De Landa, 1999: 321). The development of gaming brought new genres to the media, eventually resulting in the creation of first-person shooter games, one of the most popular forms of gaming of the 21st century, functioning in the industry for 40 years. This essay has chosen to focus on the Call of Duty franchise, more specifically the latest instalment Call of Duty: WW2 which allows the player to take control of soldiers and lead them into battle against the enemy. Since its conception in 2003, Call of Duty has become one of the top entertainment franchises in the world, with the latest instalment calming the title of Best-Selling Game in 2017 (Fortune, 2017). There have since been 23 release titles, generating in over 250 million units of sales, equating to over £10 million. As statistics suggest, each new instalment is avidly played by millions worldwide, suggesting the franchise is able to maintain a distinct level of quality in its production. Huntermann and Thomas (2010) noted the salient theme of each war game was the focus on the gun. The theorists postulated that the foremost emblem for every game representing war is what they call “the virtual gun” stating that ‘the gun is a cultural signifier of profound impact because it is so deeply embedded into contentious debates ranging from delinquency to violence, to identity politics, to virtuality’ (p.12). The virtual gun is considered semiotic, meaning the vessel is able to be altered depending on the context in which it is placed.

This use of semiotics is evident within Call of Duty, which is able to present the “virtual gun” concept effectively through game-play. As each Call of Duty game varies in location and time, the gun is able to act as a tool to reflect whatever time-frame is being presented. As the virtual gun is able to act a vessel in which the franchise can choose to project a specific identity, for example, the latest instalment of Call of Duty focuses on the Second World War, as a result, the virtual guns featured within game-play are attempts to recreate the type of weaponry that was used during that specific era. As well as being historically accurate, Call of Duty successful communicates the narrative relevant to the given time period. However, it would be wrong to assume from this example that every released title of Call of Duty is entirely historically accurate in its representations. Rather, it is implied that the popularity of the game derives from its ability to reflect the considered diverse representations of warfare. This diversity allows players to attach various forms of identity towards the game, making it more openly accessible to wider audiences.

fig.1 & 2

In the images included above, the gun is present in both images. Considering the nature of a First-person shooter game, the perspective of the player is concrete. However, the guns featured within both images are notably different. Nevertheless, both guns are able to convey a sense of time due to their virtual structure, allowing players to not only identify what era is being represented by also allowing them to call upon their knowledge of warfare and battle specific to that period.

The Introduction Video

To continue, whilst the use of the virtual gun is a prominent and effective medium for many video games, including Call of Duty, it is not the sole provider and support of context. Call of Duty heavily relies on other contextual facts in order to replicate the memory of war. As previously stated, each Call of Duty games varies in their representation of space and time, most of which is reflected through the use of imagery that is used in order to further promote a sense of war throughout gameplay. The most obvious communication of detail is found within the title, ‘WWII’. This immediately gives players a faint idea of the concepts that will exist within the game, allowing them to bring pre-existing memories and knowledge of the Second World War into play, almost encouraging their audience to reminisce about moments of the Second World War.[1] One could consider this as a construction of memory, prompting individuals to conjure up their perceptions of war which have been obtained through the experience of other external sources, these encouragements are reinforced through the use of imagery.

fig.3

[1]Note: I do acknowledge that, most likely, most avid players of call of duty do not have experience in warfare or combat. This will be discussed later within the project.

The promotional image of Call of Duty: WW2 features a close-up portrait of a white, male soldier. Whilst virtual, the detail in the image is defined, the face of the character is dirty and bloodied, assumedly obtained through battle and his eyes fixated on the audience. However defined the image, it still promotes a sense of ambiguity. Whilst there are defining characteristics which allow for these assumptions to be made, the character displayed is generic in his virtual makeup, with little signifiers to suggest era or origin. As a result, consumers are able to project a sense of identity on to this character, enabling them to elect their own factors. For example, a British player may assume this character is a citizen of the United Kingdom, therefore implying that memories specific to their culture or heritage will more likely be chosen to be reflected upon. In the example stated, the memories projected onto this character will reflect those represented within a British, Scottish, Welsh or Irish culture. The cultural ambiguity is indicative of the producer’s aims to allow players to play as a representation of themselves, taking themselves into battle.

To continue, imagery is also used to re-create a new memory of war. To this day, patriotism and military service and intricately intertwined within the minds of society. This is reflected in national days of remembrance, such as Armistice Day or Remembrance Day. Whilst this day of remembering is to signify respect for those who lost their lives to war, there are often themes of nostalgia found within the discussion of war. Nostalgia is a term used to refer to longing for the past, or ‘bygone times, or for a set of relationships and experiences associated with the past’ (MacKenzie and Foster, 2017: 208). The representation of relationships is a theme that is utilised within Call of Duty which focuses on the concept of manhood and comradery.

fig.4

Within these promotional image taken from Call of Duty: WW2, there is a sense of brotherhood as a band of men are represented in battle. In the first, one man is seen helping a fellow soldier to his feet, whilst the other depicts soldiers marching together. Although the sex or gender of these soldiers is undefined, given the context of the game promoting the idea of friendship and unity reinforcing the notion that whilst caught up within brutal warfare, relationships and bonds were strong and an integral part of combat. This nostalgic yearning for these war-time friendships is evident in other forms of media. Band of Brothers was a series broadcast in 2012 depicting the 506th Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S Army.

fig.5

This indicates that the emphasis on relationships within the war is not contained solely within Call of Duty but is a cultural phenomenon, and is an assumed norm. Furthermore, beyond this notion of comradery, the notion of ‘band of brothers’ evoked notions of determination and perseverance, proposing men swear loyalty to one another to fight tyranny, further suggesting “the band of brothers” is a strong element within the psyche. Although, there is concern surrounding the concept of nostalgia and war. Rivitoi (2002) stated that nostalgia is not simply about looking back in time; rather, it can involve idealizing and mythologizing history (cited in MacKenzie and Foster, 2017: 208). This point raised implies that this sense of nostalgia and images of brotherhood represented throughout Call of Duty may run the risk of distorting memory, idealizing forms of war that were not necessarily representative of its history. This argument is supported by Delisle who claimed that nostalgia although ‘based on individual lived experience, still may be influenced by elements of fantasy, the distortion of memory’ (2005: 17). It could, therefore, be possible that players of Call of Duty: WW2 may be subject to a misrepresentation of memory as these ‘representational frames directly involve players as actors in historical events and render these available as interactive experiences. As a consequence of this, critiques that exclusively focus on games’ historical content are often misguided’ (Pötzsch and Vìt Šisler, 2016: 4).

These findings are also evident within the opening title sequence of Call of Duty: WW2 which consists of iconic and historical images and moving clips including a march of Nazi Germany which is identifiable by the Swastika emblem.

Fig.6

Over-laying these images are extracts taken from a prayer read by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, which was broadcast over the radio the American nation during 1944, on the eve where British, American and Canadian soldiers were to take part in the battle of Normandy. These intermedia references connect the game to a historical narrative, generating an expectation of authenticity. Pötzsch and Vìt Šisler (2016) argue that these devices invite players to perceive the depicted persons, game maps, and events as realistic and based on factual historical incidents. ‘This charges the initial transition of the player into the diegetic universe with expectations of being able to act in authentic environments and to vicariously experience simulated history first-hand’ (p.8).

Fig,7

Whilst virtual warfare, according to the Call of Duty creative team, is not aimed at providing a true reflection of real events, this then suggests that those who are avid players of the Call of Duty series are so because they are more likely to be attracted to the authenticity and historical accuracy advertised. ‘According to self-reports, the game created an immersive and motivating learning environment and that enabled a transformation of history from abstract, yet authoritative, entity into idiosyncratic personal experiences and individuals life stories susceptible to interactive engagements by players’ (Pötzsch and Vìt Šisler, 2016: 18). Likewise, according to Chapman (2012) games and other forms of simulations not only must ‘inherent potential to convey certain historical facts but in particular raise awareness for the ultimate contingency of any recollection of the past’. With this being said, this anticipation for historical accuracy is the only present due to the cultural memory that exists within players, as a result, creators face pressure to meet the standards of accuracy. On the other hand, the presence or absence of realistic or historical content has potential to affect how players attach or generate meaning. Any inaccuracies identified within the game would, therefore, allow for new definitions of meaning to be made. This does not diminish existing cultural memories of war but instead offers alternative memory and perspective.

The Campaign: D-Day

The campaign is a feature prominent within all different forms of Call of Duty, it allows players to play either on their own or through cooperative gameplay, rather than competing for points players are thrown into a story-line, usually relating to the context in which the game is placed. Call of Duty: WW2 campaign opens on June 6th, 1944, the historic invasion of the Normandy beaches that resulted in the liberation of France. More widely referred to as D-Day, this operation has since been labelled as the largest land, air, and naval to have occurred throughout history. This campaign places players into the character of Ronald “Red” Daniels, a U.S soldier from Texas. The campaign follows a concrete narrative arc, which for the most part of the game is eschewed in favour of developing the main character and his relationship with fellow characters, whilst using the varying battlefields as the backdrop. This further reinforces the notion that was discussed earlier that the element of comradery and brotherhood are key elements within the American psyche. Also, this may almost be construed as an attempt to excuse any inaccuracies featured within the campaign. Perhaps done in an attempt to entice players become more invested within the emotion of the characters rather than the historically accurate representation

D-Day has become one of the most famous operations in the history of the Second World War, resulting in the construction of multiple memorials being built in order to preserve the legacy and memory of the operation. This cultural formation reinforces the idea that D-day holds a significant role within cultural and collective memory. Halbwachs (1992) argued that the notion of memory is a matter of how minds worth within society, ‘it is in society that people normally acquire their memories. It is also in society that they recall, recognise, and localise memories’ (p.38). Relating to the memory of D-Day, given its historical value and resonance, society has chosen to recall and localise the memory of the operation in the form of constructing memorials and memorial days. Therefore, replicating a memory that is so easily recognised would assumedly be easy as well as accurate due to the detail that exists within these present memories. The virtual construction of D-day was more than likely adapted from images that already existed within the media, resulting in an authentic virtual world for players.

Fig 8 & 9

The images here are stills taken from the opening moments of the campaign, where players are first introduced to the playable character Ronald Daniels. Witnessing the scenes through the eyes of Ronald, the campaign opens on the soldiers travelling towards the shores of Normandy by boat. The images given here are an attempt at re-creating a physical photo taken on D-Day. Additionally, this virtual creation is not re-imagining nor distorting the players’ memory of D-Day, instead offering a synthetic experience of the environment. ‘Reconstruction through real and digital platforms, given form through creative efforts, re-presents a new “real” world to the viewers, one that is continuously compared to the memory and narratives of the lost world’. (Aceti, 2009: 17).

Fig 10 & 11

This photograph taken by Robert Capa, taken on Omaha beach on June 6th, 1944 was presented alongside 11 other images. These images are referenced as being iconic, providing insight into the invasion of the Germany-occupied territory. During the campaign, creators never state which beach of Normandy is featured in the campaign, rather the statement reads as ‘Normandy beaches, France’. This allows creators to be vague in their representations of the past. The ambiguity enables a sense of reality to be constructed that can be applied to any memory that relates to the event. Through the omission of a location, the campaign is able to be representative of them all. As memory is claimed to be subjective, players are then able to project their memory and understanding of D-day onto the world in front of them, some may imagine they are playing on the beach Juno beach whilst another may be battling on the sands of Sword beach.

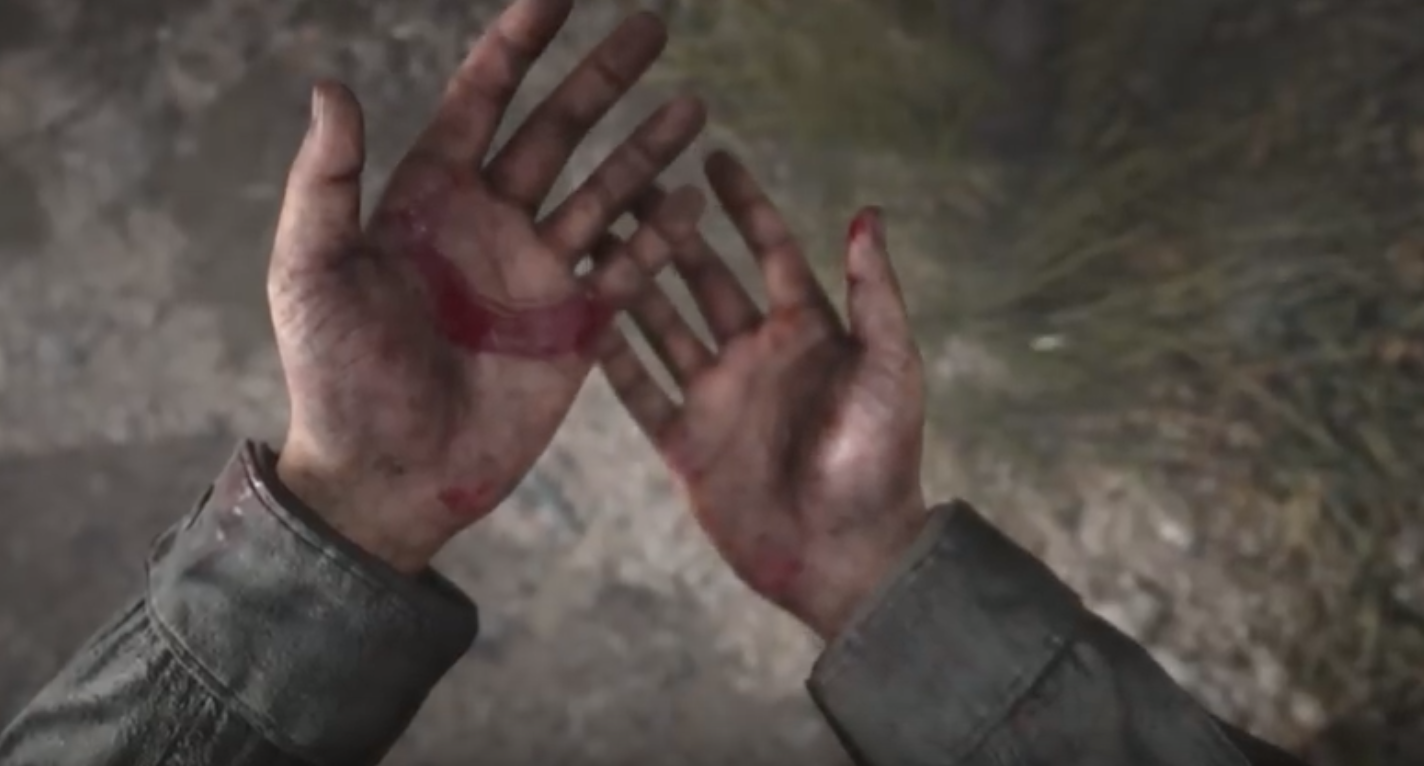

Maintaining a sense of accuracy is supposedly very important for the game developers of Call of Duty. However, the plain fact being that this is still just a video game hinders the development of representation. As it has been discussed, Call of Duty has not necessarily altered nor re-imagined the memory of the past but offered an opportunity to experience a synthetic version of history. Conversely, this has only been done to some extent. Indeed, what has been done is somewhat accurate, but let us not forget that a high proportion of those who play Call of Duty are more than likely to have never experienced physical combat or warfare, as we know their memories and knowledge of the war can be obtained through culture and other external sources, such as education. Yet they lack the memory of emotion, making them free of the haunting stress of war. The game attempts to recreate this emotion within their campaign, in which the playable character, Ronald, is seen to kill an enemy soldier with his bare hands in a bid to save his life. Players must fight to fend off their rival, eventually having to beat him to death with a helmet. Afterwards, players then must drag their injured comrade to safety, in which the camera pans down to show the players their hands covered in blood.

Fig.12

In what is assumed to be an extremely raw and emotional moment within the campaign, Ronald Daniels is forced to face the brutal nature and murderous reality of war. However emotive this scene attempts to be, it only highlights that memory can only stretch so far. Whilst players may empathise with their character, they are free to leave the game whenever they choose, walking free of the trauma whilst their character, who is representative of millions of soldiers, is trapped within the haunting memory of war. This reminds us, Call of Duty is not a simulation. It is a game, a game to be played. Players are able to remain unattached to the post-traumatic stress and return to reality.

In conclusion, whilst it was thought at the beginning of this project that Call of Duty altered the memory of the war in some way it has come to my attention than rather than distort memories of war, Call of Duty has instead re-created and re-imagined existing memories. This has resulted in a virtual world that enabled players to engage in a, somewhat, accurate feel of the Second World War and allowing them to witness, on some level, the memories they have obtained within society. It is interesting to find that through its preservation, war has almost become a commodity within this form of media. Whilst people gain a sense of pleasure, indulging in a world of nostalgia the true reality and nature of war is lost in the action and authenticity. Call of duty has been able to create a way for people to play within the history of the Second World War. On the other hand, this playable part of history only highlights the notion that whilst memory can be synthetically manufactured, the true emotion and experience cannot. This is perhaps why Call of Duty is so popular, it provides all the heroism without the trauma.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aceti, L. (2009). Without Visible Scars: Digital Art and the Memory of War. Leonardo, [online] 42(1), pp.16-26. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/20532585.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ac91f4479323e4e75654a6fcb765835b4.

Assmann, J. and Czaplicka, J. (1995). Collective Memory and Cultural Identity on JSTOR. [online] Jstor.org. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/488538.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Aa0791e6b4643610bcd035da0510b0a54 [Accessed 18 Apr. 2018].

Chapman, A. (2012). Privileging form over content: Analysing historical videogames.

Journal of Digital Humanities, 1. Retreived from http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/

1-2/privileging-form-over-content-by-adam-chapman/

Huntemann, N. and Payne, M. (2010). Joystick soldiers. New York: Routledge, pp.12-15.

MacKenzie, M. and Foster, A. (2017). Masculinity nostalgia: How war and occupation inspire a yearning for gender order. Security Dialogue, [online] 48(3), pp.206-223. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0967010617696238.

Mastin, L. (2018). The Human Memory – what it is, how it works and how it can go wrong. [online] Available at: http://www.lukemastin.com/humanmemory/ [Accessed 18 Apr. 2018].

Pötzsch, H. and Šisler, V. (2016). Playing Cultural Memory. Games and Culture, [online] pp.8-18. Available at: https://munin.uit.no/bitstream/handle/10037/10439/article.pdf?sequence=6.

Wilson, K. (2006). FROM MEMORY TO HISTORY: AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY OF THE VIETNAM WAR. [ebook] Miami University Oxford, Ohio, pp.3-55. Available at: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=miami1153500782&disposition=inline [Accessed 20 Apr. 2018].

Images Used:

Call of Duty (n.d.). Fig. 3 Game Image. [image] Available at: https://www.callofduty.com/uk/en/ [Accessed 20 Apr. 2018].

CBS Interactive Images (2018). Fig 4, 5: Promotional Images. [image] Available at: https://www.gamespot.com/call-of-duty-wwii/images/ [Accessed 20 Apr. 2018].

Magnum Photos (n.d.). Fig. 10: Robert Capa © International Center of Photography US troops’ assault on Omaha Beach during the D-Day landings. Normandy, France. June 6, 1944. © Robert Capa © International Center of Photography | Magnum Photos. [image] Available at: https://www.magnumphotos.com/newsroom/conflict/robert-capa-d-day-omaha-beach/ [Accessed 20 Apr. 2018].

Paste Magazine (2017). Fig. 10 D-day Campaign. [image] Available at: https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2017/11/defusing-d-day-how-call-of-duty-wwii-undermines-wh.html [Accessed 20 Apr. 2018].

Photo of Soldiers approaching Normandy, June 6th 1944. Fig.9(2018). [image] Available at: https://www.historyonthenet.com/d-day/ [Accessed 20 Apr. 2018].

The Game Shed (2014). Fig, 2. [image] Available at: http://www.thegamesshed.com/call-duty-advanced-warfare/ [Accessed 20 Apr. 2018].

VG247 (2017). Fig 1. Gun Image. [image] Available at: https://www.vg247.com/2017/06/14/call-of-duty-ww2-multiplayer-gameplay-revealed-watch-the-new-war-mode-killstreaks-divisions-more/ [Accessed 20 Apr. 2018].

YouTube (2017). Fig 6, 7 ,8, 12: Campaign Images. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=edvnX8TwSTI [Accessed 20 Apr. 2018].

Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=edvnX8TwSTI [Accessed 20 Apr. 2018].